When I was a child of the sixties and seventies, we enjoyed much our time outside of the house playing with the other neighborhood children when possible during our leisure. We did not have the benefits of what today’s kids can partake in, the electronic activities that can now entertain them; we on the other hand had to make it up as we went along using whatever inspiration we could draw upon. Not having the assortment and variety of today’s markets for playtime fun, we had to create, invent, and use our own imaginations for filling in the time at hand. Much of our imaginations were filled up with the stories we had heard as children about exploration from Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone, to other historical figures which fueled our pioneering appetites. On occasion we also had to play indoors when it rained or just because we wanted to use materials inside the house to create our own forts, the very infamous bed sheet fort that so many other kids imagined as well.

Much of my time I spent outside in the neighborhood canyons creating elaborate outdoor tree forts, climbing dangerous cliffs, having dirt-clod fights, carving tree wood into walking staffs and other wood weapons such as spears, and exploring the terrain as if I were a great explorer. Countless times I would find myself in the canyons of my home and play for endless hours in the acres and acres of untouched hilly canyon wilderness of the California landscape. Much of this desire was to challenge the landscapes obstructions and Tera-formed it to my own needs. Day-dreams of a boy being out in the wilderness comprised much of my thoughts as I explored the outdoors and the inner dreams of my childhood.

Amazed at the stories I would learn about as a boy, I often dreamed of the real hardships people have faced for many years, and for many years to come.

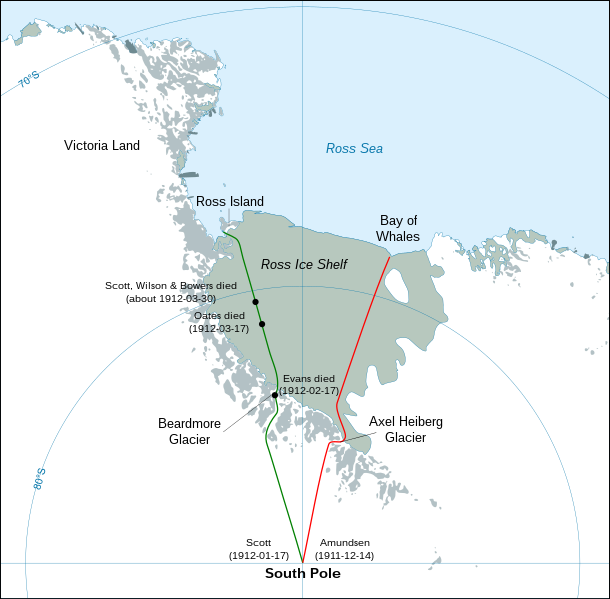

Robert Falcon Scott led the Ill-famed Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13. During this venture, Scott led a party of five which reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, only to find that they had been preceded by Roald Amundsen’s Norwegian expedition. On their return journey, Scott and his four comrades all died from a combination of exhaustion, starvation and extreme cold.

Much of the expedition was surrounded by bad weather, miscalculations and failures to provide contingency plans for events that could likely befall the team on their race to the South Pole.

The expedition itself suffered a series of early misfortunes, which hampered the first season’s work and impaired preparations for the main polar march. On its journey from New Zealand to the Antarctic, Terra Nova was trapped in pack ice for 20 days, far longer than other ships had experienced, which meant a late-season arrival and less time for preparatory work before the Antarctic winter. One of the motor sledges was lost during its unloading from the ship, breaking through the sea ice and sinking. Deteriorating weather and weak, acclimatised ponies affected the first depot-laying journey, so that the expedition’s main supply point, One Ton Depot, was laid 35 miles (56 km) north of its planned location at 80° S. Lawrence Oates, in charge of the ponies, advised Scott to kill ponies for food and advance the depot to 80° S, which Scott refused to do. Oates is reported as saying to Scott, “Sir, I’m afraid you’ll come to regret not taking my advice.” Six ponies died during this journey either from the cold or because they slowed the team down so they were shot. On its return to base, the expedition learned of the presence of Amundsen, camped with his crew and a large contingent of dogs in the Bay of Whales, 200 miles (320 km) to their east.

Scott refused to amend his schedule to deal with the Amundsen threat, writing, “The proper, as well as the wiser course, is for us to proceed exactly as though this had not happened”. While acknowledging that the Norwegian’s base was closer to the pole and that his experience as a dog driver was formidable, Scott had the advantage of traveling over a known route pioneered by Shackleton. During the 1911 winter his confidence increased; on 2 August, after the return of a three-man party from their winter journey to Cape Crozier, Scott wrote, “I feel sure we are as near perfection as experience can direct”.

Scott outlined his plans for the southern journey to the entire shore party,but left open who would form the final polar team. Eleven days before Scott’s teams set off towards the pole, Scott gave the dog driver Meares the following written orders at Cape Evans dated 20 October 1911 to secure Scott’s speedy return from the pole using dogs:

About the first week of February I should like you to start your third journey to the South, the object being to hasten the return of the third Southern unit [the polar party] and give it a chance to catch the ship. The date of your departure must depend on news received from returning units, the extent of the depot of dog food you have been able to leave at One Ton Camp, the state of the dogs, etc … It looks at present as though you should aim at meeting the returning party about March 1 in Latitude 82 or 82.30

The march south began on 1 November 1911, a caravan of mixed transport groups (motors, dogs, horses), with loaded sledges, travelling at different rates, all designed to support a last group of four men who would make a dash for the Pole. The southbound party steadily reduced in size as successive support teams turned back. Scott reminded the returning Atkinson of the order “to take the two dog-teams south in the event of Meares having to return home, as seemed likely”. By 4 January 1912, the last two four-man groups had reached 87° 34′ S. Scott announced his decision: five men (Scott, Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers, Lawrence Oates and Edgar Evans) would go forward, the other three (Teddy Evans, William Lashly and Tom Crean) would return. The chosen group marched on, reaching the Pole on 17 January 1912, only to find that Amundsen had preceded them by five weeks. Scott’s anguish is indicated in his diary: “The worst has happened”; “All the day dreams must go”; “Great God! This is an awful place”.

C. 1/17/1912

The deflated party began the 800-mile (1,300 km) return journey on 19 January. “I’m afraid the return journey is going to be dreadfully tiring and monotonous”, wrote Scott on the next day. However, the party made good progress despite poor weather, and had completed the Polar Plateau stage of their journey, about 300 miles (500 km), by 7 February. In the following days, as the party made the 100-mile (160 km) descent of the Beardmore Glacier, the physical condition of Edgar Evans, which Scott had noted with concern as early as 23 January, declined sharply. A fall on 4 February had left Evans “dull and incapable”,and on 17 February, after a further fall, he died near the glacier foot.

Meanwhile back at Cape Evans, the Terra Nova arrived at the beginning of February, and Atkinson decided to unload the supplies from the ship with his own men and not set out south with the dogs to meet Scott as ordered. When Atkinson finally did leave south for the planned rendezvous with Scott, he met the scurvy-ridden Edward (“Teddy”) Evans who needed his urgent medical attention. Atkinson therefore tried to send the experienced navigator Wright south to meet Scott, but chief meteorologist Simpson declared he needed Wright for scientific work. Atkinson then decided to send the short-sighted Cherry-Garrard on 25 February, who was not able to navigate, only as far as One Ton depot (which is within sight of Mount Erebus), effectively cancelling Scott’s orders for meeting him at latitude 82 or 82.30 on 1 March.

With 400 miles (670 km) still to travel across the Ross Ice Shelf, Scott’s party’s prospects steadily worsened as, with deteriorating weather, frostbite, snow blindness, hunger and exhaustion, and no sign of the dog-teams, they struggled northward. On 16 March, Oates, whose condition was aggravated by an old war-wound to the extent that he was barely able to walk,voluntarily left the tent and walked to his death. Scott wrote that Oates’ last words were “I am just going outside and may be some time”.

After walking a further 20 miles, the three remaining men made their final camp on 19 March, 11 miles (18 km) short of One Ton Depot, but 24 miles (38 km) beyond the original intended place of the depot. The next day a fierce blizzard prevented their making any progress. During the next nine days, as their supplies ran out, with frozen fingers, little light, and storms still raging outside the tent, Scott wrote his last words, although he gave up his diary after 23 March, save for a last entry on 29 March, with its concluding words: “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”. He left letters to Wilson’s mother, Bowers’ mother, a string of notables including his former commander Sir George Egerton, his own mother and his wife. He also wrote his “Message To The Public”, primarily a defense of the expedition’s organization and conduct in which the party’s failure is attributed to weather and other misfortunes, but ending on an inspirational note, with these words:

“We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence,determined still to do our best to the last … Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for.” — Robert Falcon Scott

The challenges in life are often endured and beaten on the terms of those whose dreams go answered. There are those who dare to dream and in doing so sometimes do not foretell the risk and danger of these dreams that go unanswered, and ensue an untimely end. There is something very profound in the human spirit that compels us from an early age to seek adventures, challenge nature, and ourselves. From the modest dreams of a Southern California boy to the Antarctic British explorer there lies a fundamental wanton provocation to go beyond the unknown. The endurance of dreams and the dream to endure seems to be rooted deeply within us, no matter what part of the world we live in, or what part of the world we affront.

You must be logged in to post a comment.